Buffalo Soldiers on Bicycles 1896-1897

Carmon Weaver Hicks, Ph.D.

George Hicks, III

December 2012

To see this documentary in action, go to - http://watch.montanapbs.org/video/1499356776/

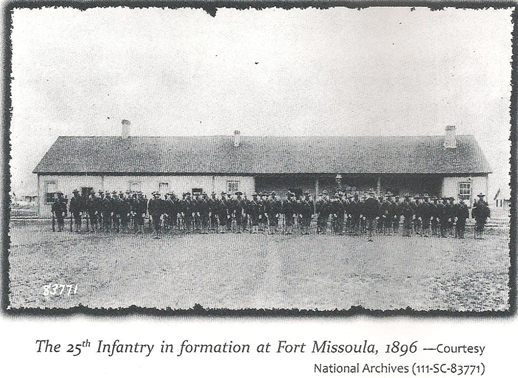

In 1888, Ft. Missoula in Missoula, Montana became the home of the 25th Regiment of the US Army – known as the Buffalo Soldiers. For several years, they were assigned to stop Indian disturbances, guard trains, and maintain order during labor disputes among coal miners and railroad workers. Their lives were structured and included drills, and chores, participating in marches, and shooting practice; constructing and repairing buildings on the post; caring for their horses and mules; and serving on guard duty six days a week.

According to the editor of the Anaconda Standard newspaper, “they were model soldiers when in garrison and their conduct whenever they have been called into the field has been excellent.” The soldiers planted vegetable gardens and went fishing and hunting for fresh meat. In addition, every black regiment was assigned a chaplain who conducted religious services and taught the soldiers to read, write and do math. Their lives were decent when compared to other African Americans during these times.

Lt. James Moss, a US Military Academy graduate in 1894, finished last in his class and was assigned to this undesirable post in Montana. Due to his undistinguished record, he wanted to make his mark on the military. He suggested an experiment to test whether bicycles could be used instead of horses to transport soldiers. Horses had many disadvantages - they needed food, water, and rest. They could die or be killed – leaving the soldier without transportation. And, sometimes they made noise that alerted the enemy or panicked during battle. Bicycles were becoming popular and Gen. Nelson Miles at army headquarters believed that bicycles had potential for use in the Army. The US Army approved the creation of the Bicycle Corps.

Pvt. John Findley, who had worked at Imperial Bicycle Works in Chicago, stepped up to join the Corps. Not only did he know how to ride bicycles but he knew how to repair them. The 25th Infantry Experimental Bicycle Corps consisted of eight enlisted men – Sgt. Dalbert Green, Cpl. John G. Williams, Pvt. Frank L. Johnson, Pvt. William Proctor, Pvt. William Haynes, Pvt. Elwood Forman, musician William Brown, and Pvt. John Findley.

Lt. Moss took six men on the first 126-mile (round trip) to Lake McDonald – about 50 miles north of the fort. They took about 120 pounds of food, cooking and eating utensils, extra clothes, personal care items, and bicycle repair parts and tools – all strapped to their bikes. Bedrolls and tents were strapped to their handlebars and each soldier carried a rifle and 50 pounds of ammunition. On August 6, 1896, the Bicycle Corps ventured north from Ft. Missoula. The weather was rainy and the roads were muddy. Steep hills were slick and often trees blocked their path. In many locations, they were forced to walk their bicycles along the railroad tracks; however, they traveled approximately 50 miles that day and arrived at Mission Creek. The Bicycle Corps attracted a lot of attention; horses and cows ran away, dogs chased them, and people stopped work in astonishment as they gazed at the soldiers riding by.

The next afternoon, they arrived at their destiny - Lake McDonald. This lake is hemmed in by mountains whose tops tower into the clouds. The lake was full of trout and several soldiers who brought fishing lines caught them as fast as they could pull them out. Lt. Moss’ journal notes indicated that the beautiful scenery and excellent fishing made up for the difficult journey. The rain continued that night and as they headed back the next day. Their wet uniforms were heavy, their bikes struggled through rough roads, and their shoes were filled with mud. They stopped frequently to repair their bikes – nuts were tightened, handlebars and chairs adjusted, and 12 loose tires were cemented back into the wooden bicycle rims.

They finally reached Ft. Missoula on August 9 – having traveled 126 miles in four days. Lt. Moss considered this trip a success in spite of the many obstacles. The bicycles stood up well to the test and the soldiers proved their stamina. This journey showed what these soldiers could accomplish. Six days later, they were headed out for their next journey.

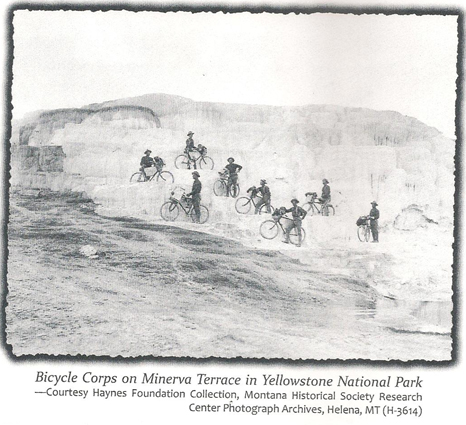

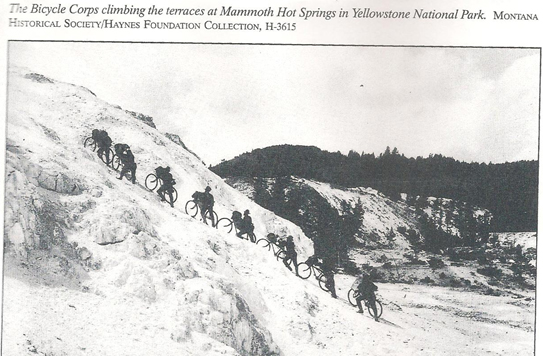

On August 15, 1896, the second experiment included all eight members of the Corps as they headed 325 miles east to Yellowstone National Park – the first national park in the world. In 1872, President Ulysses Grant signed a bill into law setting land aside for Yellowstone. This was an opportunity for these soldiers to see the hot springs and geysers that were considered the greatest spectacle in the West. To help document the trip, Moss took a Kodak camera and seven rolls of film. As they traveled across Montana, townspeople were surprised to see a group of African American soldiers riding bicycles; they were friendly to the men and cheered them on.

They met the famous artist, Frederic Remington, who was riding with another Buffalo Soldier unit from Fort Assinboine, Montana. Remington was surprised one morning. He looked up and saw Lt. Moss and the Buffalo Soldiers Bicycle Corps pedaling along, followed by another infantry unit on foot. In an article for The Cosmopolitan Magazine, he wrote – After breakfast, the march begins. A Bicycle Corps pulls out ahead. It is heavy wheeling and pretty bumpy on the grass, where they are compelled to ride, but they managed far better than one would anticipate…

The Bicycle Corps averaged about 45 miles each day - over rough terrain - and arrived at Ft. Yellowstone in 8 ½ days. They spent a week resting, touring the park, picnicking, and fishing. Clearly, they enjoyed themselves and when they reached the Continental Divide, half of the group stood on one side and shook hands with the men on the other side.

Their return trip began on September 1 where they ran into heavy rain on the first and second days which created several bicycle mechanical problems. On the third day, the sun came out and they travelled 72 miles. The next several days, the wind was strong and the roads were bad but they reached Ft. Missoula on September 8 – traveling 790 miles. Moss was pleased with the trip ad noted that the soldiers were treated royally everywhere.

On September 13, the Bicycle Corps conducted a small-scale maneuver with another unit of the 25th Infantry. Logistical tactics were practiced which expanded their scope; cyclist scouted ahead of the line and set up a courier service. Cyclists stationed at intervals along a 15-mile stretch relayed messages about possible campsites, water availability, and road conditions.

Each day, one cyclist was detailed to bring up the rear so that he could report accidents or delays.

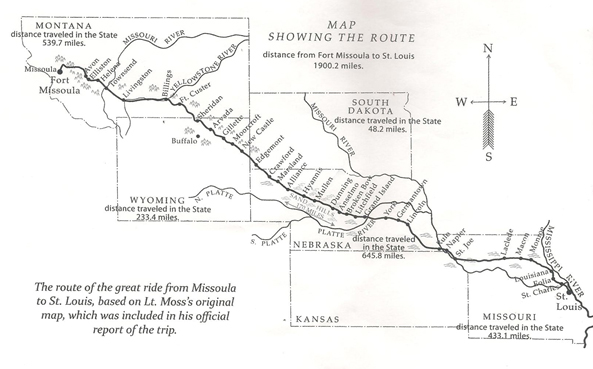

The next trip was the biggest challenge – 1900 miles halfway across the continent from Ft. Missoula, Montana to St. Louis, Missouri. This route passed through low and high altitudes, moist and dry climates, upgrades and downgrades, the mountains of Montana, the hummock earth roads of South Dakota, the sandy roads of Nebraska, and the clay roads of Missouri. Lt. Moss wanted to show the top military men the usefulness of bicycles in the US Army.

The Bicycle Corps was physically demanding but 40 men volunteered. Moss selected 20 men – ranging in age from 25-39. Army regulations stated that cyclists must weigh no more than 140 pounds and be no taller than 5 feet, 8 inches. Several of the men selected did not meet these criteria but Moss was given special permission to include them. Only five of the original cyclists were part of the new group. The final list included:

| Sgt. Mingo Sanders | Pvt. William Proctor |

| Lance Cpl. William Hayes | Pvt. Elwood Forman |

| Lance Cpl. Abram Martin | Pvt. Richard Rout |

| Musician Elias Johnson | Pvt. Eugene Jones |

| Pvt. John Findley | Pvt. Sam Johnson |

| Pvt. George Scott | Pvt. William Williamson |

| Pvt. Hiram L.B. Dingman | Pvt. Sam Williamson |

| Pvt. Travis Bridges | Pvt. John Wilson |

| Pvt. John Cook | Pvt. Samuel Reid |

| Pvt. Frank L. Johnson | Pvt. Francis Button |

Because it was a long and hazardous journey, the fort’s physician, Dr. James M. Kennedy and a newspaper reporter from The Daily Missoulian, Edward Boos, joined the group. Pvt. Findley served as the mechanic and his bicycle was heavier since it was fitted with a metal toolbox. The Spalding Bicycle Company lent Moss bicycles that were the most modern design at the time. They had steel frames and rims, tandem spokes, reinforced side forks and crowns, gear cases, luggage carriers, and chains that were covered with rubber casing for protection. Each bicycle also had a top-of-the-line Christy saddle. This design had a split seat with a slightly recessed channel down the center which was constructed to conform to a man’s anatomical parts. This improved seat design increased their comfort and injury to the rider from the saddle was nearly impossible. The Corps tested eight different brands of tires during their journey. Each bike was equipped with 59 pounds of food, supplies, and equipment. They departed on June 14, 1897.

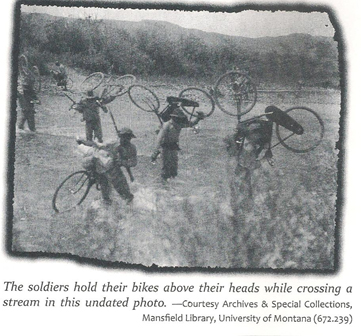

On the first day, they rode 54 miles in a rainstorm that turned the roads to mud. The second day, the rain continued but they rode more than 50 miles – often dismounting and walking. They experienced bad weather, rough roads, and mosquitos. Sometimes the soldiers tried to pedal over the railroad tracks and if the encountered a big body of water, they carried their bicycles on their shoulders. This time when they reached the Continental Divide, they faced blowing snow and freezing temperatures. Nevertheless, when they entered small, rural towns, the people were curious – some had never seen African American soldiers. They often received food, supplies, and places to stay. As they continued to travel east, the Bicycle Corps attracted larger crowds; people were interested in them and wanted to inspect their wheels. Often, they made the front page of local newspapers.

On day 10, the Corps reached Billings, Montana. The next day, June 25, 1897, they rode a short distance to Little Bighorn Battlefield to see the place where Gen. George Custer and the 7th Cavalry fought their last battle against Northern Cheyenne and Sioux warriors. It is believed that 268 of the nearly 600 men in Custer’s command died. Of the 10,000 Indians involved, of which 2000-3000 were estimated to be warriors, only 150 or so were lost. The loss of Custer, his brother, and the other soldiers was one of the greatest shocks of that era – equal in its impact to the assassination of a president or a space shuttle explosion. The date of the Bicycle Corps’ visit marked the 21st anniversary of Custer’s fatal fight. The soldiers were silent as they observed dozens of small white tombstones scattered across the field.

The men traveled through Wyoming, South Dakota, and Nebraska but the roads and the weather never improved. Bike damage and minor illnesses put them behind schedule. On the 3rd of July, they received a warm welcome in Crawford, Nebraska. In a double-line formation, they pedaled down the main street while the band played and the crowd cheered. Soldiers from nearby Fort Robinson met the Corps and provided entertainment as well as assisted them with bicycle repairs. The next day, they celebrated in Alliance, Nebraska which marked their 1000 mile mark. Pedaling through Nebraska, the temperatures reached 110 degrees and little water could be found. In some cases, their handlebars were too hot to hold. Some of the men got sick from drinking alkaline water, including Lt. Moss, who was left behind. Later when Moss and the sick soldiers recovered, they took a train and went about 100 miles ahead to give themselves more time to recover before re-joining the riders.

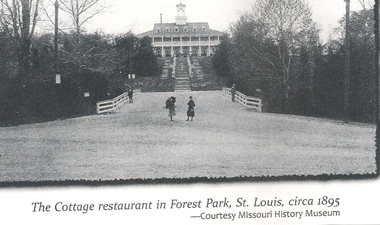

On July 16, they reached the Missouri River and took a ferry across the river. The Missouri roads were the worst of the trip. They rode in furnace-like heat, continuing to lack good water. Everyone was fatigued to the point of exhaustion during the last few days. When they reached St. Louis on July 24, 1897, the end was finally in sight. They were met by a squad of mounted police who led the way down Union Ave. to Forest Park – a great expanse of green in the center of St. Louis.

The 1900 mile journey officially ended at the Cottage restaurant in Forest Park, Missouri. Lt. Moss gave his last order of the trip – You will now rest wheels and fall in for mess. More than 500 people came to the restaurant to watch them eat dinner. Their journey was highlighted in a variety of newspapers which reported that more than 10,000 people visited the Bicycle Corps at their camp. A reception was arranged in their honor and the Buffalo Soldiers performed a drill at the Associated Cycling Club. An entourage of 300 local riders accompanied the men to the YMCA to watch them perform drills. The next day, a parade traveled through town. The participants consisted of a squad of mounted police, the Branch Guard Bicycle Corps, the 25th US Infantry Bicycle Corps, the City Streets Committee of the League of American Wheelmen, Associated Cycling Clubs, and unattached riders.

The trip took 40 days of which 34 days were spent traveling. The average speed registered 6.3 mph covering 55.9 miles per day. Lt. Moss sent a letter to the War Department asking that the Bicycle Corps continue to St. Paul, Minnesota but his request was denied. After resting for a week, the soldiers returned to Ft. Missoula by train arriving on August 19, 1897. Lt. Moss praised his men for their “spirit, plunk, and fine soldierly qualities.” He noted that the journey “tested… not only their physical endurance but their moral courage and disposition.”

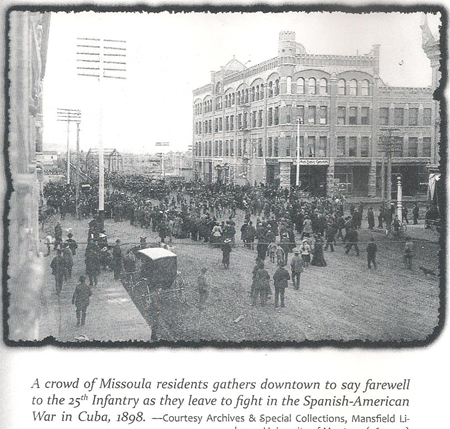

Tensions between the United States and Spain had been brewing and on February 15, 1898 the US battleship, Maine, exploded in the harbor at Havana, Cuba. The call to war rang out. The 25th Infantry was one of the first units ordered to Cuba. On Easter Sunday, April 15, 1898, troops left Ft. Missoula for training camps in Georgia and Florida. That morning, the citizens of Missoula lined the streets to say goodbye; the outpouring of support was impressive.

The 25th Infantry served honorably in Cuba.

In 1974, two professors from the Black Studies Department at the University of Montana, Pferron Davis and Richard Smith, organized a trip to honor the 25th US Infantry Bicycle Corps. On June 14, the 77th anniversary of the Corps departure, 10 cyclists followed the soldiers’ journey from Missoula to St. Louis. This time, on paved streets and highways watching traffic - their biggest concern – they faced the same steep hills and bad weather. Doss noted that “it was not until we pedaled down their shadows that we could fully appreciate what they endured.”

References

Moore, K. (2012). The great bicycle experiment: The army’s historic black bicycle corps, 1896-97. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing Company.

Sorensen, G. N. (2000). Iron riders: Story of the 1890s Fort Missoula buffalo soldiers bicycle corps. Missoula, MT: Pictorial Histories Publishing Co., Inc.